Why you can't make double eye contact

Your eyes can only converge on a single point. Up close, that means you have to pick one of the other person's eyes to look at.

Have you ever noticed that when you’re face-to-face with someone, you can’t actually look at both of their eyes at the same time? You’re always picking one — left or right — and subtly switching between them.

This isn’t a limitation of attention or focus. It’s geometry.

One convergence point

Your two eyes can only aim at a single point in space at any given moment. This is called vergence — the inward rotation of both eyes to fixate on the same target. It’s what gives you depth perception, and it’s physically limited to one target at a time.

When someone is close to you, their two eyes occupy noticeably different positions in your visual field. The angular separation between them is large enough that you can’t fit both into the single point your eyes converge on. So you pick one.

Try it yourself

Toggle between looking at each eye, and slide the distance to see how angular separation changes.

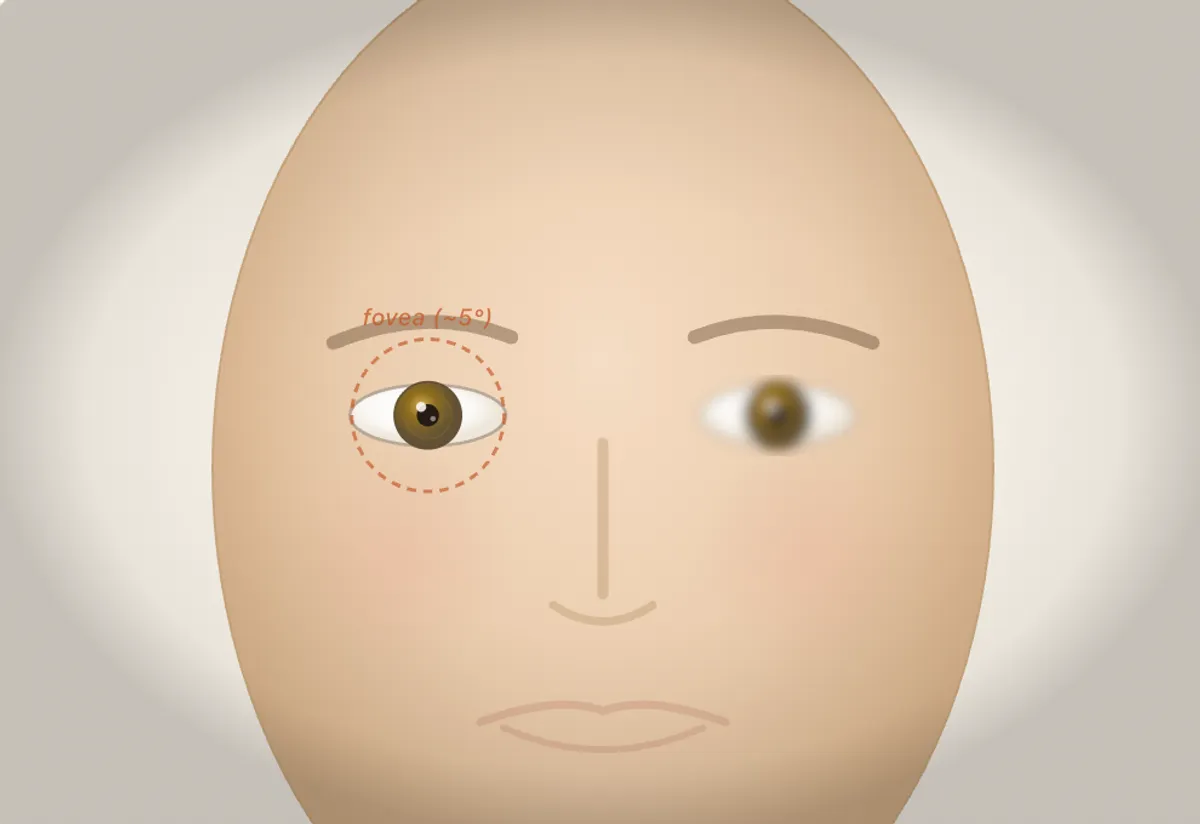

When the face is close, the angular separation between their eyes is large — well beyond your fovea (the high-resolution center of your vision, ~1.5mm across or roughly 5° of visual angle). You’re clearly choosing one eye.

As the face moves farther away, both eyes fall into a tighter angular range. Eventually they’re so close together in your visual field that it feels like you’re looking at both — even though you’re still converging on a single point.

Why it doesn’t matter at a distance

Human interpupillary distance averages about 63mm. At 1 meter away, that subtends roughly 3.6°. At 3 meters, it’s about 1.2° — easily within your fovea’s ~5° span. This is why you barely notice the effect in normal conversation but absolutely feel it during an intimate close-up.

I never would have built an interactive visualization to explore a random curiosity like this before. But with Claude Code, describing what I wanted and getting a working widget took a couple hours — so why not? The idle question gets a better answer when you can play with it yourself.